Salt runs the show in vegetable fermentation. You only have two ways to use it. Either you mix salt straight into the vegetables and let them release their own liquid, or you make a saltwater brine and pour it over the top. That is it. Every recipe you have ever seen is just a variation of one of these two approaches.

Most beginners do not know when to use which method, and they end up with soggy pickles, dry kraut, or brine levels that never look right. Old timers never struggled with this because they understood the nature of the vegetable in front of them. Some vegetables carry plenty of water and only need salt. Others need the extra help of a brine.

Once you understand the difference between dry brining and wet brining, you can pick the right method every time and get clean, crisp, reliable ferments without guessing.

What Is Dry Brining

Dry brining is the oldest way to ferment vegetables because it uses nothing but salt and the water already inside the produce. You sprinkle salt directly onto shredded or thin sliced vegetables, then work it in with your hands. The salt draws water out through osmosis. That liquid becomes your brine. No added water. Just the vegetable’s own juices pulled out by salt.

On a chemical level, the salt breaks down the cell walls enough for the moisture to escape. As the liquid rises, it creates an anaerobic environment where the right bacteria thrive and the wrong ones die off. This is why dry brining gives such a clean and deep flavor. The brine is literally the essence of the vegetable.

Traditionally, dry salting was used with vegetables that already carry plenty of water. Cabbage for sauerkraut. Shredded carrots. Sliced radishes. Beets. Anything that releases liquid when salted and squeezed.

Old school tip: Massage the salt until you see the cabbage start to sweat. If your palms look wet within a minute or two, you have hit the right point. This was the test long before kitchen scales were common.

Best Vegetables for Dry Salting

- Cabbage

- Carrots

- Radishes

- Beets

- Daikon

- Turnips

- Any shredded or thin sliced vegetable with plenty of water

Pros of Dry Brining

- Stronger and more concentrated flavor

- Crunchier texture

- Cleaner tasting brine

- Salt penetrates deeply

- Brine self adjusts because it comes from the vegetable itself

Cons of Dry Brining

- Not enough moisture in low water vegetables

- Beginners often undersalt or oversalt

- If you do not work the salt in long enough, you will not get enough liquid

- Some vegetables need too much force or time to draw out enough brine

What Is Wet Brining

Wet brining means you mix salt with water, create a controlled brine, and pour it over the vegetables. The saltwater protects the vegetables from oxygen and feeds the right bacteria so the ferment stays safe. This method solves one problem: some vegetables cannot make their own brine no matter how much you salt them.

Traditionally, wet brining is used for whole or chunky vegetables that hold their shape. Cucumbers. Green beans. Whole peppers. Garlic. Okra. Anything firm or dense.

Old school tip: Use cool well water or filtered water. Hard water makes cleaner brine. Soft water can cloud and soften vegetables faster.

Best Vegetables for Wet Brining

- Cucumbers

- Green beans

- Peppers

- Garlic

- Okra

- Cherry tomatoes

- Carrots in sticks or chunks

- Any vegetable too firm or dry to release enough water

Pros of Wet Brining

- Works on any vegetable

- Easy to scale up for big jars

- Reliable for whole vegetables

- Great for beginners

- More predictable salt levels

Cons of Wet Brining

- Dilutes the flavor slightly

- Texture can soften faster

- Must measure salt percentage correctly

- Vegetables tend to float and need weights

Salt Ratios for Both Methods

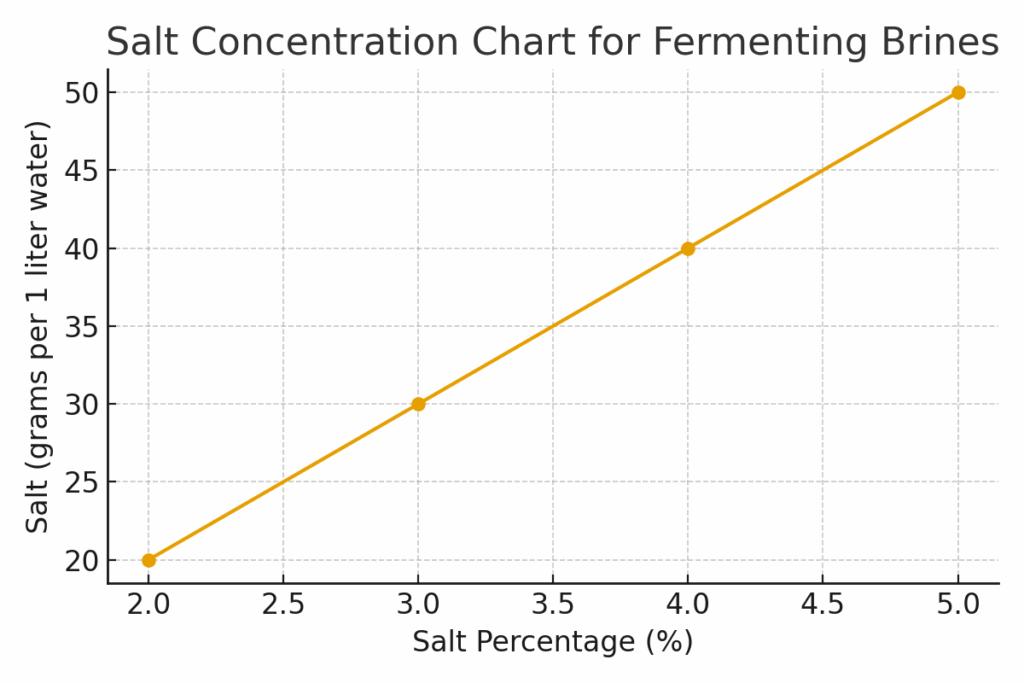

- Dry salting: two to two point five percent of vegetable weight

- Wet brine: two to five percent salt depending on the vegetable and recipe

If you want exact numbers, see the salt ratio guide. For a basic overview of safe fermentation practices, see the National Center for Home Food Preservation.

Old school note: Old timers judged brine strength by taste alone. Today we measure for safety and consistency, but learning to taste brine is still useful. A two percent brine tastes lightly salted. A five percent brine tastes firm and sharp.

Which Method Should You Use

- If the vegetable is shredded or sliced thin, use dry salting.

- If the vegetable is whole or chunky, use a wet brine.

Dry brining uses the vegetable’s own water. Wet brining gives support to vegetables that cannot release enough water on their own. Follow that rule and you will rarely choose wrong.

Troubleshooting

Not enough liquid from dry salting

Add a pinch more salt and keep massaging. If still dry, add a small splash of brine at two percent.

Vegetables floating in wet brine

Use a weight. Remove air pockets. Make sure every piece stays submerged.

Cloudy brine

Often normal. Caused by active fermentation, minerals, or softer water.

Brine too salty

Dilute with filtered water. Measure the new percentage.

Brine too weak

Add more salt. Stir gently so you do not disturb the ferment too much.

Can you switch mid recipe

Yes. If dry salting fails to release enough water, add a measured brine. If wet brine is too much, drain some brine and pack tighter.

Closing

Once you understand these two methods, fermentation becomes predictable instead of frustrating. Dry salting gives you the deepest flavor. Wet brining gives you flexibility and control. Many households used both depending on what was coming out of the garden.

Try each method a few times. You will start to understand the feel of the vegetables, the smell of a good brine, and the rhythm that old school fermenters knew by instinct.